|

All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 2

All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 3

Equine conformation evaluates the degree of correctness of a horse's bone structure, musculature, and its body proportions in relation to each other. Undesirable conformation can limit the ability to perform a specific task. Although there are several universal "faults," a horse's conformation is usually judged by what its intended use may be. Thus "form to function" is one of the first set of traits considered in judging conformation. A horse with poor form for a Grand Prix show jumper could have excellent conformation for a World Champion cutting horse, or to be a champion draft horse. Every horse has good and bad points of its conformation and many horses (including Olympic caliber horses) excel even with conformation faults.

Conformation of the Head and Neck

The Head

The standard of the ideal head varies dramatically from breed to breed based on a mixture of the role the horse is bred for and what breeders, owners and enthusiasts find appealing. Breed standards frequently cite large eyes, a broad forehead and a dry head-to-neck connection as important to correctness about the head. Presumably, the construction of the horse's head influences its breathing, though there are few studies to support this. Historically, a width of 4 fingers or 7.2 cm was associated with an unrestricted airflow and greater endurance. However, a study in 2000 which compared the intermandibular width-to-size ratio of Thoroughbreds with their racing success showed this to be untrue. The relationship between head conformation and performance are not well-understood, and an appealing head may be more a matter of marketability than performance. Among mammals, morphology of the head often plays a role in temperature regulation and water balance. As one of the relatively few mammals that sweat, it is unlikely that a horse's head conformation plays a significant role in water balance. Many ungulates have a specialized network of blood vessels called the carotid rete, which keeps the brain cool while the body temperature rises during exercise. Horses lack a carotid rete and instead use their sinuses to cool blood around the brain. These factors suggest that the conformation of a horse's head influences its ability to regulate temperature but not water balance.

Descriptive Terms for Head Types

Dished face on an Arabian

The horse has a concave or "dished" profile, often further emphasized by slight bulging of forehead (jibbah). Dished heads are associated with Arabians and Arabian-influenced breeds, which excel at endurance riding and were originally bred in the arid Arabian desert. There are several theories regarding the adaptive role of the dished head. It may be an adaptation to reduce airflow resistance and increase aerobic endurance. It may also have a role in cooling inspired air, or cooling blood headed to the brain.

Roman Nose/Shires often have a Roman nose

The horse has a convex profile (Roman Nose). Convex heads are associated with Draft horses, Baroque horse breeds and horses from cold regions. This trait likely plays a role in warming air as it is inhaled, but may also influence aerobic capacity.

Faults of the Head

Pig Eye

A small eye, primarily an aesthetic issue, but claimed by some to be linked to stubbornness or nervousness, and thought to decrease the horse's visual field. Sometimes this may be referred to as an "Appy eye." (Appaloosa)

Overshot jaw (parrot mouth) or undershot jaw ("monkey jaw" or "sow mouth")

Parrot Mouth (left) and Undershot, Monkey Mouth or Sow Mouth (right)

Often seen in horses that also have narrow jaws and muzzle. The upper jaw extends further out than the lower jaw, with the horse having an overbite (parrot mouth), or the lower jaw extends farther out than the upper jaw, with the horse having an underbite (sow mouth). Both defects can affect the chewing of the horse and the horse's ability to graze. Both defects are fairly rare.

Small Nostrils

Opening of the nostrils (the nares) is narrow and somewhat restricted, limiting ability to expand the nostrils for breathing while working hard. May occur in any breed. Especially affects horses in high-speed activities (polo, racing, eventing, steeplechase) or those that need to sustain effort over long duration (endurance, competitive trial, combined driving). These horses are therefore best for pleasure riding or non-speed sports.

Short Neck

The ideal neck is about 1/3 horse's length, measured from poll to withers, with a length comparable to the length of the legs. A neck that is less than 1/3 the length of the horse. Short necks are common, and seen in any breed. A short neck is often quite flexible despite appearing thick and muscular, and the function and range is rarely altered. May be slightly less flexible at the poll, but the horse's maneuverability and agility are generally not affected. It does not shorten stride length, which has more to do with shoulder slope. The horse may not excel at jumping high obstacles or galloping at high speeds, and may not be as handy at quick directional changes.

Long Neck

A long neck is a neck is one that is much more than 1/3 the length of the horse. Long necks are common, especially in Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, and Gaited Horse. It may make it hard to balance the horse, and the horse may fatigue more quickly as a result of carrying too much weight on its front end.

Lengthy neck muscles are difficult to develop in size and strength. A long-necked horse needs broad withers to support the weight of head and neck.

It is easier for the horse to fall into the bend of an S-curve than to come through the bridle, which causes the horse to fall onto his inside shoulder. This makes him difficult for the rider to straighten. The horse is best for jumping and speed sports (without quick changes of direction), or for straight line riding like trail riding.

Excessively Large/Crest

The horse has an overly large crest that may fall to one side in extreme cases. Relatively uncommon, although any horse can develop an excessively large crest. It is usually seen in stallions, ponies, Morgans, and draft breeds. It is usually from fat deposits above the nuchal ligament. An excessively large crest not only looks bad, but it puts more weight on the forehand. A horse with excessive crest due to obesity needs a proper conditioning program.

Bull neck: Short and Thick

The horse has a short, thick, and beefy neck with short upper curve. The attachment to its body is beneath the half-way point down the length of shoulder.

This trait is fairly common, especially in draft breeds, Quarter Horses, and Morgans. It is generally more difficult to maintain balance if the rider is large and heavy or out of balance, which causes the horse to fall onto its forehand. Without a rider, the horse is usually fine. A bull neck is desirable for draft or carriage horses, so as to provide comfort for the neck collar. The muscles of the neck also generate pulling power. The horse is best for non-speed sports.

Ewe-neck, with muscling on the underside. (Ewe Neck/Upside-down Neck/with muscling on the underside)

A neck with internal structure that causes it to bend upward instead of down in the normal arch. This fault is common and seen in any breed, especially in long-necked horses but mainly in the Arabian Horse and Thoroughbred. The fault may be caused by a horse who holds his neck high (stargazing). Stargazing makes it difficult for a rider to control the horse, who then braces on the bit and is hard-mouthed. An ewe neck is counter-productive to collection and proper transitions, as the horse only elevates its head and does not engage its hind end. The horse's loins and back may become sore. The sunken crest often fills if the horse is ridden correctly into its bridle. However, the horse's performance will be limited until proper muscling is developed.

Swan Neck

The horse has a neck set at a high upward angle, with the upper curve arched, yet a dip remains in front of the withers and the muscles bulge on the underside. This conformation type is common, especially in Saddlebreds, Gaited horses, and Thoroughbreds. A swan neck makes it easy for a horse to lean on the bit and curl behind without lifting its back. Often caused by incorrect work or false collection.

Arched/Turned-over Neck

The crest is convex or arched with proportional development of all muscles. This is an ideal neck. Common, seen in all breeds and in all sports. The neck appears as if it is flowing into the back, so it looks good and creates an efficient lever for maneuvering. The strength of the neck with proportional development of all muscles improves the swing of shoulder, elevates the shoulder and body, and aids the horse in engaging its hindquarters through activation of the back. Good for any sport.

Knife-Necked

A long, skinny neck, with poor muscular development on both the top and bottom. Appearance of a straight crest without much substance below. Any breed can be affected. It is sometimes seen in young, green horses. It is usually associated with poor development of back, neck, abdominal and haunch muscles, allowing a horse to go in a strung-out frame with no collection and on its forehand. It is often rider-induced, and usually indicates lack of athletic ability. It can be improved through skillful riding and the careful use of side reins to develop more muscle and stability.

The horse is best for light pleasure riding until its strength is developed.

Horizontal Neck

The neck is set on the chest neither too high nor too low, with its weight and balance aligned with the forward movement of the body. Although relatively uncommon, it is usually seen in Thoroughbreds, American Quarter Horses, and some Warmbloods. Advantageous to every sport, as the neck is flexible and works well for balancing. The neck is not too bulky, thin, long, or short. The horse is easy to supple, develop strength, and to control with hand and legs aids. Conformation of the chest, shoulder, and forearm.

The Shoulder

Upright shoulder/Straight, Upright, or Vertical Shoulder

The shoulder blade, measured from the top of the withers to the point of shoulder, lies in an upright position, particularly as it follows the scapular spine. Often accompanies low withers. Upright shoulders are common and seen in any breed, particularly Quarter Horses. An upright shoulder affects all sports. The horse has shorter muscular attachments that thus have less ability to contract and lengthen. This shortens the stride length, which requires the horse to take more steps to cover ground, and thus causes a greater risk of injury to structures of front legs and hastened muscular fatigue. An upright shoulder may cause a rough, inelastic ride due to the high knee action. It increases concussion on front limbs, possibly promoting the development of DJD or navicular disease in hard-working horses. The stress of impact tends to stiffen the muscles of the shoulder, making the horse less supple with a reduced range of motion needed for long stride reach.

An upright shoulder causes the shoulder joint to be open and set low over a short, steep arm bone, making it difficult for a horse to elevate its shoulders and fold its angles tightly, which is needed for good jumping, or in cutting. A horse with an upright shoulder usually does not have good form over fences. The horse is usually easier to accelerate in sprinting. An upright shoulder is best for gaited or park showing, parade horses, and activities requiring a quick burst of speed, like roping or Quarter Horse racing.

Laid-back or Sloping Shoulder

Upright Shoulder

The horse has an oblique angle of shoulder (measured from the top of the withers to the point of shoulder) with the withers set well behind the elbow. Often accompanies a deep chest and high withers. A sloping shoulder is common. It mostly affects jumping, racing, cutting, reining, polo, eventing, and dressage.

The horse has a long shoulder blade to which attached muscles effectively contract and so increase the extension and efficiency of stride. It distributes muscular attachments of the shoulder to the body over a large area, decreasing jar and preventing stiffening of the shoulders with impact. The horse has an elasticity and free swing of its shoulder, enabling extension of stride that is needed in dressage and jumping. A long stride contributes to stamina and assists in maintaining speed. The longer the bones of the shoulder blade and arm, the easier it is to fold legs and tuck over fences. The laid back scapula slides back to the horizontal as the horse lifts its front legs, increasing the horse's scope over fences. A sloping shoulder has better shock-absorption and provides a comfortable ride because it sets the withers back, so a rider is not over the front legs. A sloping shoulder is most advantageous for jumping, dressage, eventing, cutting, polo, driving, racing, and endurance.

The Humerus (Arm Bone)

The arm bone is from the point of shoulder to the elbow, and its length dictates how tightly the elbow and lower joints can bend and reach for extension.

Long Arm Bone

The humerus is long when it is 50-60% of the length of the scapula. The elbow is beneath the middle of the withers if the humerus is long. This conformation mostly affects jumping, steeplechase, eventing, lateral movements of dressage, and cutting. A long humerus increases movement of elbow away from torso, both forward and to the side, allowing more tucking over fences and increased stride in speed events. It provides a scaffold for lengthy muscle attachments of flexor and extensor muscles, which contract with greater force to increase power and speed. Best suited for speed events, jumping, and dressage.

Short Arm Bone

Humerus is usually in a horizontal position which closes the shoulder angle (shoulder and humerus) to less than 90 degrees. Common, usually seen in Quarter Horses, Paints, and Warmblood. A short humerus decreases the scope of a horse, and contributes to a short, choppy stride. This increases the impact stress on front legs, especially the feet. The rider is jarred and the horse absorbs a lot of concussion. More steps are needed to cover ground, increasing the chance of front-end lameness. The horse tends to be less able to do lateral movements. Advantageous for sprinting sports Horse is best used for pleasure riding, non-impact activities, and sprinting sports like roping or barrel racing.

The Forearm (Radius)

Long Forearm

The length of the radius (between elbow and carpus) is long. Seen in all breeds, especially Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, Tennessee Walkers, Arabians, and Warmbloods. A long forearm is desirable for any performance activity, especially if the horse also has a short cannon. It increases the surface area and length of muscular attachments to gain best leverage for maximum stride length and speed. Good muscling of a long forearm is especially advantageous to jumping horses, as the strong forearm muscles absorb concussion from the impact and diffuse the strain on tendons and joints on landing. A long forearm is best for speed events, jumping events, and long distance trail riding.

Short Forearm

The distance of radius from elbow and carpus is proportionately short. Although uncommon, it is usually seen in Morgans and Quarter Horses. A short forearm affects speed and jumping events, but has little effect on stock horse events. The length of stride is dependent on the forearm length and shoulder angle, so a short forearm causes horse to need to increase the number of steps to cover a distance, increasing overall muscular effort and hastening fatigue. Increases the action of the knees, giving an animated appearance. Knee action is not compatible with speed. Best for showing, hunter equitation, harness, parade.

Tail

High Tail Set

Tail comes out of body on a level with the top of the back. Commonly seen, usually in Arabians, Saddlebreds, Gaited horses, and Morgans. There is no direct performance consequence. Often, although not always, it is associated with a flat croup. A high-set tail contributes to the appearance of a horizontal croup, which may be an aesthetic concern to some. Gives as animated appearance, which is good for parade, showing, or driving.

Low Tail Set

Tail comes out of the body well down along the haunches. Associated with goose-rumped or steep pelvis. Seen in any breed, especially in draft breeds. Only aesthetic concern unless directly caused by pelvic conformation.

Wry Tail/Tail Carried to One Side

The tail is carried cocked to one side rather than parallel to the spine. May be linked to spinal misalignment, possibly due to injury. May be because the horse is not straight between the rider's aids, can be used to determine how straight a horse is traveling behind. Over time, incorrect body carriage may place undue stress on limbs. May be from discomfort, irritation or injury. This can also be caused by neurological problems from disease or injury.

Ribcage and Flanks

Wide Chest and Barrel/Rib Cage

Rounded ribs increase the dimensions of the chest, creating rounded, cylindrical or barrel shape to the rib cage. Length of the ribs tends to be short.

Seen in any breed, especially American Quarter Horses, and some Warmbloods. Provides ample room for the expansion of the lungs. Too much roundness increases the size of the barrel, may restrict upper arm movement, the length of stride, and thus speed. Round ribs with a short rib length further restrict the shoulder.

Pushes the ride's legs further to the side of the body, and can be uncomfortable, especially in sports that require long hours in saddle or that require sensitive leg aids (dressage, cutting, reining).

Pear-Shaped Ribcage/Widens Toward Flank

The horse is narrow at and behind the girth at midchest, then widens toward the flank. Common, especially in Arabians, Saddlebreds, and Gaited horses. Makes it difficult to hold the saddle in place without a breastplate or crupper, especially on uneven terrain, jumping, or low crouch work with quick changes of direction (cutting). When saddle continually shifts, the rider's balance is affected, and the horse and rider must make constant adjustments. Saddle slippage has the potential to create friction and rubs on back or cause sore back muscles. Horse is best used in sports on level terrain and for non-jumping activities.

Well-Sprung Ribs

Ribs angle backward with sufficient length, breadth, and spacing with arched rib cage and deep chest from front to back. Largest part of the barrel is just behind the girth area. Last rib is sprung outward and inclined to the rear, with the other ribs similar in length, roundness, and rearward direction.

Desirable for any sport. Promotes strong air intake, improving performance and muscular efficiency. Ample area of attachment of shoulder, leg and neck muscles, enabling a large range of motion for muscular contraction and speed of stride. The rider's weight is easily balanced and stabilized since the saddle stays steady and the rider can maintain close contact on horse's side with leg. There is sufficient room for developing strong loin muscles while still having short loin distance between last rib and point of hip (close coupling).

Slab-Sided

Poor spring of the ribs due to flatness and vertical alignment of the ribs. Ribs are adequate in length. Common, especially in Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, Tennessee Walkers, and Gaited horses. There is less room for the lungs to expand, limiting the efficiency of muscular metabolism with prolonged, arduous exercise

If there is a short depth in the chest, the horse will have a limited lung capacity which is likely to limit the horse's ability for speed work

Horse generally has lateral flexibility. Narrowness makes it difficult for the rider to apply aids since the legs often hangs down without fully closing on the horse. More effort needed to stay on horse's back because of limited leg contact and the saddle tends to shift Horse has a harder time carrying the rider's weight because of reduced base of support by narrow back muscles.

Tucked Up/Herring-gutted/Wasp-Waisted

Waist beneath the flanks is angular, narrow, and tucked up with a limited development of abdominal muscles. Often associated with short rear ribs, or undernourished horses. Seen in any breed. Often a result of how horse is trained and ridden. If a horse does not use its back to engage, they never develop their abdominal muscles. Appears to be like a lean runner (greyhoundish), with stringy muscles on topline and gaskin. Lack of abdominal development reduces overall strength of movement. Stamina is reduced, and the back is predisposed to injury. The horse is incapable of fluid, elastic stride, but is probably capable of ground-cover despite correct body carriage. Speed and jumping sports should be avoided until the muscles are developed.

Good Depth of Back

The depth of the back is the vertical distance from lowest point of back to bottom of abdomen. Point in front of sheath or udder should be parallel to the ground and comparable in depth to front portion of chest just behind the elbow at the girth. Seen in any breed, especially Warmbloods, Quarter Horses, and Morgans.

Good depth indicates strong abdominal muscles, which are important for strength and speed. Critical to dressage, jumping, and racing. Strong abdominals go with a strong back, which is suitable for carrying a rider's weight and engaging the haunches. Should not be confused with an obese horse in "show" condition, as fat just conceals wasp-waistedness.

Conformation of the Hindquarters and Hips

The Hindquarters

Slight Hindquarters

Short Hindquarters - Measured from the point of hip to the point of buttock, the hindquarters should be ideally at least 30% of length of overall horse. Anything less is considered short. Most horses are between 29-33%; Thoroughbreds may have a length reaching 35%. Insufficient length minimizes the length of the muscles needed for powerful and rapid muscular contraction. Thus, its reduces speed over distance, stamina, sprint power, and staying ability. Tends to reduce the horse's ability to fully engage the hindquarters need for collection or to break in a sliding stop. Horse is most suited for pleasure sports that do not require speed or power.

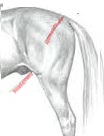

Steep-Rumped

Viewed form the side, the pelvis assumes a steep, downward slope Uncommon, except in draft horses, but seen in some Warmbloods A steep slant of the pelvis lowers the point of buttock bringing it closer to the ground " shortening the length of muscles from the point of buttock " the gaskin. Shortens the backward swing of the leg because of reduced extension & rotation of hip joint. A horse needs a good range of hip to get a good galloping speed and mechanical efficiency of hip and croup for power " thrust. Therefore, a goose-rumped horse is not good at flat racing or sprinting. Harder for a horse to "get under" and engage the hindquarters. Causes the loins and lower back to work harder, predisposing them to injury A goose-rump is valuable in sports with rapid turns " spins (reining, cutting). The horse is able to generate power for short, slow steps (good for draft work). Horse is most suited for stock horse work, slow power events (draft in harness), low speed events (equitation, pleasure, trail).

Goose-Rumped

Viewed from the side, the pelvis has a relatively flat, but sloping profile of adequate length, but the flatness does not extend to the dock of the tail as in a Flat-Crouped horse Common in some Warmbloods and may be considered a desirable trait in some breeds This conformation allows good engagement of the hindquarters, while giving the long stride and speed of Flat-Crouped conformation. Often associated with good jumping performance. Note that the term Goose-Rumped is sometimes used as a synonym for Steep-Rumped, potentially causing confusion, as the two conformations imply rather different qualities in the horse's performance.

Cat-Hammed/Frog's Thighs

The horse has poor development in the hindquarters, especially the quadriceps and thighs. Associated with goosed-rumps and sickle hocks. Uncommon, most usually seen in Gaited horses. Can develop from years in confinement. The horse lacks the development needed for speed and power, so the horse is not fast or strong. Thus it is not advantageous for flat racing, polo, eventing, jumping, steeplechase, and harness racing. The horse's gait tends to be more ambling than driving at the trot, so the horse often develops a stiff torso and back, making the ride rigid.

The Hips

Narrow Hips

Viewed from the rear, the breadth between the hips is narrow. Common, seen in any breed, although Quarter Horses tend not to have them. Usually in Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, Arabians, and Gaited horses. A narrow pelvis contributes to speed since the horse can get its hind legs well under its body to develop thrust.

The narrow hip shape is partially dictated by exercise development of haunch muscles. Good width widens the breadth between stifles, hocks and lower legs to enable power, acceleration, and foot purchase into ground, preventing interference injuries. Narrow pelvis limits size of muscular attachments of hips, affecting strength and power. The horse is best suited for flat racing, trail, carriage driving.

Rafter Hips

Wide, flat hip shaped like a "T" when viewed from behind. Cattle tend to have this pelvis type to the extreme. Uncommon, usually seen in Gaited horses, Saddlebreds, and Arabs. Rafter hips are often amplified by poor muscling along thighs and lower hips. Exercises to improve muscling helps the problem.

One Hip Bone Lower/Knocked-Down Hip

From behind, the point of hip on one side is lower than the other. May be due to an injury to the point of hip, or to sublaxtion or fracture of the pelvis.

Uncommon. Generally induced by a traumatic blow to hip. Not heritable. The gait symmetry is affected (which is bad for dressage or show horses). Interference with power and thrust may alter strength of jumping high fences or reduce speed. The horse is more prone to developing muscular or ligament soreness associated with re-injury or strain. This is especially likely to occur in a jumper, racer, steeplechaser, or eventer. However, in most cases the horse recovers completely.

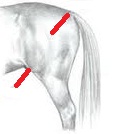

High Stifles/Short Hip

A horse with a high stifle has a hip shaped sort of like the top of a turkey drumstick

Ideal hip forms equilateral triangle from point of buttock, point of hip, and stifle. A short hip has a short femur (thigh bone) that reduces the length of quadriceps and thigh muscles. The femur is short when the stifle seems high (sits above sheath in male horse). Found in any breed, but usually in racing Quarter Horses or Thoroughbreds. Effective in generating short, rapid, powerful strokes (sprint or draft work). The horse has a rapid thrust and thus rapid initiation of sprint speed. Ideally, the bones of the gaskin and femur should be of similar length in horse that does anything but sprint or draft work. A short femur reduces stride length behind and elasticity of stride that jumpers, dressage horses, and flat/harness racers want.

Low Stifle/ Long Hip

A horse with a low stifle has a square thigh area

A long hip is created by a long femur which drops the level of stifle to or below the sheath line on a male horse. Favorable in all sports except sprint sports and draft work Enables the horse to develop speed and power after it gets moving. The muscles of the hip, haunches, and thighs will be proportionately long with a long hipbone, giving the horse the capacity to develop speed and power over a sizeable distance. Produces ground-covering and efficient stride in all gaits.

Good for eventing, steeplechase/timber, flat/harness racing, jumping, and long distance riding.

For More Information:

All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 2

All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 3

Horse Physiological Problem Chart

|